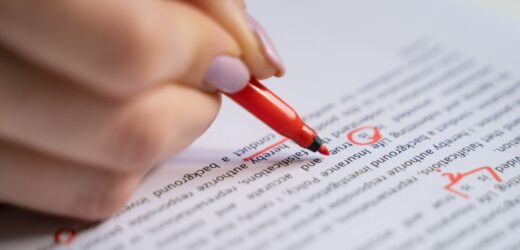

When we return work to our students, we hope that they will study our feedback carefully and strive to improve their writing on the next assignment. Indeed, there are times when faculty may observe a student receiving a paper, looking for the grade, and then throwing the paper (with all its feedback) in the trash. Sometimes the students may not have thrown the paper out, but it seems to us that they might as well have done so: many faculty read a second or third round of papers that seem to lack even a trace of evidence that we had given feedback on the first paper at all.

Actionable Feedback in the Undergraduate Curriculum

Related Articles

I have two loves: teaching and learning. Although I love them for different reasons, I’ve been passionate about...

Could doodles, sketches, and stick figures help to keep the college reading apocalypse at bay?...

We’ve all faced it: the daunting stack of student work, each submission representing hours of potential grading. The...

Storytelling is one of the most powerful means of communication as it can captivate the audience, improving retention...

For some of us, it takes some time to get into the swing of summer. Some of us...

About a year ago, I decided to combine the ideas of a syllabus activity and a get-to-know-students activity....

The use of AI in higher education is growing, but many faculty members are still looking for ways...