Teachers can’t monitor what’s happening in multiple groups. Students, on the other hand, know exactly what’s happening in their group—who’s contributing what in the group as well as what they’re doing. From that position they can make judgments and offer peers feedback. The potential benefits of their doing so include self-assessment skill development, more engagement with group processes, and acceptance of the responsibility for learning. But empirical substantiation of those benefits is scant, with indications that feedback effects may vary depending on whether the feedback offers praise or criticism; whether it focuses on the task, group processes, or self-assessments; and whether it focuses on past actions or offers advice for the future. This study addresses one gap in the research. Does the exchange of feedback between students enhance teamwork and self-assessment abilities? The answer may offer evidence that confirms the assumed value of self- and peer assessment in the context of group work.

Does Self- and Peer Assessment Improve Learning in Groups?

Related Articles

I have two loves: teaching and learning. Although I love them for different reasons, I’ve been passionate about...

Imitation may be the sincerest form of flattery, but what if it’s also the best first step to...

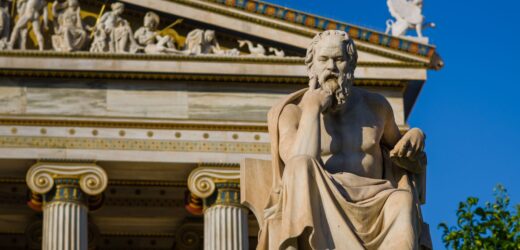

Higher education has long recognized the value of Socratic dialogue in learning. Law schools traditionally adopt it in...

After 35 years in higher education, I continue to embrace the summer as a prime opportunity to strengthen...

Last month I wrote about how students fool themselves into thinking they have learned concepts when they really...

If you’ve ever hesitated to offer feedback to a colleague for fear of creating tension or hurting a...

When I first began teaching online, I thought creating engaging and relevant content was the biggest challenge. And...